| |

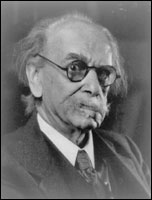

| Franz Boas (c. 1940). Library of Congress | |

Boas contributed in many different venues to the rise of a cosmopolitan worldview, one in which intellectuals and other educated Americans aspired to a new culture that would combine the best features of other cultures existing in the world. He nurtured a skepticism about received cultural categories, and that inspired not only those people who were interested in dismantling scientific racism as a doctrine but also a younger generation of women anthropologists who as feminists were interested in dismantling the Victorian gender system.

Boas's work as a scholar, an anthropologist, and a public figure influenced the ideas of two younger intellectuals, Horace Kallen and Randolph Bourne, who came of age in the second decade of the twentieth century. The positions that Kallen and Bourne articulated about the consequences of ethnic diversity for American national identity are still with us today and still inform debates about American multiculturalism and national culture.

German-American anthropologist. Boas was born in Minden, Germany, and received a Ph.D. from the University of Kiel (1881). His earliest fieldwork was devoted to Eskimos and Native Americans of Canada. He began teaching at Columbia University in 1896 and was a member of the faculty until 1936. At Columbia he founded the first department of anthropology in the United States and taught and inspired a generation of anthropologists, notably Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Against the nineteenth-century idea of an evolutionary scale leading from savagery to "culture," Boas developed the theoretical framework known as cultural relativism. An early critic of the use of race as an explanation in the natural and social sciences, he emphasized instead the importance of environment and the effort to understand societies through their particular histories. His methods and conclusions are still widely influential. Among Boas's many works are The Mind of Primitive Man (1911) and Anthropology and Modern Life (1928).

Content excerpted from Intellectual and Cultural History of the United States, 1890-1945: Ethnic Pluralism, with Casey Nelson Blake.